T T S L K

DOOR 305 Collective Artists

June 02, 2021

TTSLK

WRITTEN BY Carlomar Arcangel Daoana

Triangulations of Art

The triangle, one of the basic shapes of geometry, has long been used in the language of art. As an invisible framework, it allows for the illusionistic rendition of three-dimensional space on a flat surface through the single-point perspective. The shape also organizes figurative details in an arrangement called “triangular composition.” Its symbolic value conveys hierarchy (Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs), the development of the classic narrative plot (Freytag’s Pyramid), and God Himself (The Eye of Providence). In architecture, next to the hexagon, the triangle offers the most stable building block for the built environment.

In TTSLK,a group exhibition by the Door 305 Artist Collective, the triangle becomes the organizing principle, both on visual and metaphorical levels, in the works of Aldron Anchinges, Revelio Bueno, Celdrick Dela Paz, Yhana Dela Paz, Rhoss Gadiana, Mark Laza, Christian Maglente, Arnel Natividad, Ricky Natividad, Francisco Ochoco, Jolo Senese, and Macj Turla. Through the prism of this shape, the artists contemplate various issues, ranging from environmental degradation to the ills of society to existential reckoning of life and death.

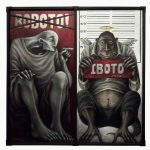

In his work, “Sakalam,” Anchinges presents how poverty, evoked by a child who gets meager sustenance from fishbone, remains as one of the most pressing problems in the country, further complicated by the incursions of the Chinese into our territories as they drive away our fishermen. For C. Dela Paz, the root cause of our problems is the systemic failure of elections to enshrine effective leaders, giving power instead to the evidently corrupt, as depicted in his work, “Palsipikadong Kandidato, Kwalipikadong Pakitang-Tao.” An active engagement with society is the initial step to finding solutions to our problems, as implied by Gadiana in “Buhay” and Y. Dela Paz in “Walks of Life” as both of them depict body parts (hands and feet) that permit labor and mobility. A dire consequence of inaction, such as when OFWs are left without support, may lead to death, something that is powerfully conveyed by Laza in “Repatriated.”

For A. Natividad, R. Natividad, and Senese, the environment remains to be the most urgent concern, as this directly impacts not just humans but the rest of creation. In Senese’s “Ailurophile,” one is presented with a surreal pop imagery of a woman strumming a guitar as anthropomorphic cats listen along. Amid the solace of music is a handful of trees cut down, which symbolizes man’s indifference to his surroundings. In “Alab ng Pag Dinig,” R. Natividad presents the tree as something magical and archetypal, which holds the fire of life. A. Natividad, on the other hand, presents the dystopic view of the world in the absence of trees, populated instead by the ugly structures of the urban landscape.

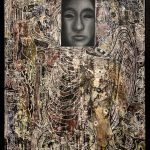

An investigation into the interior state of man characterizes the works of Bueno, Maglente, Ochoco, and Turla. In light of the pandemic, mental health issues have surfaced, as confronted by “Help, Can’t Sleep; Sleep Can’t Help” by Bueno. Submerged in half-dark, a stylized view of a woman is shown dealing with her inner demons during a bout of insomnia, her thoughts trickling out like milk. In “Stop Waiting for May,” Ochoco offers a more pro-active way of dealing with one’s own internal struggle by joining the hectic commotions of world and not wait for more suitable season, as what the month of May symbolizes. While the invitation to enjoy life remains, thoughts of mortality always assail the individual, as evoked by the depictions of skulls and skeletons by Maglente in “I Am Above” and XOX by Turla.

Members of the Door 305 Artist Collective artists show their preference on figuration, but not its straight-out realism. Each of them—whether through the use of symbols, text, surreal details, painterly elements, and inventive cropping—extends the visual language in order to articulate their inner thoughts and feelings (“saloobin”) that directly impact not only the individual but the Filipinos as a whole. Aware of the power relations present in all aspects of life (the elite vs. the masses, the urban vs. the rural, the oppressor vs. the oppressed), the artists translate the imbalance of forces in TTSLKwith a view of flipping over the social pyramid.