AMPO

MICHAEL DELMO

JULY 25 - AUGUST 6, 2020

AMPO

WRITTEN BY JAY BAUTISTA

Painting on a Prayer

Oftentimes to espouse the contemporary, artists painstakingly create alternative realities of their own making. From organic cast of subjects, to ethereal settings, even backing them up with personal myths and mythologies as main conniving narratives.

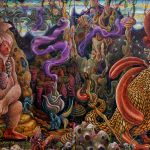

In his second solo exhibition AMPO (Hiligaynon for prayer) Michael Delmo contemplates further his artistic direction on this ongoing pandemic and pursues his faith in an inner spiritual vision wrought by whimsical creatures in eerie landscapes.

For Delmo, art-making is a form of an in-depth religious undertaking–manifesting your full potential as a way of coping and even surviving these difficult and trying times. These seven paintings reveal a long hollowing narrative how Delmo has interpreted the coronavirus as a menace and as an imaginative tactic of revenge that the inherent good in people will eventually prevail.

The story goes there was once a world where inhabitants were living in harmony. In Sakíyo (steal) an alien creature arrives and imposes a grim influence of greed and terror to the community. The alien creature resembles how the coronavirus has appallingly enveloped our habitat. At the same time he has started to paint for this exhibition, Delmo cleverly establishes the similar parallel act to how even the

coronavirus today also came from a foreign country.

Íwag (light) features a mysterious ray of light that has alerted the inhabitants signaling there is gravely something wrong with their surroundings. Pangáyam (hunt) announces a cause for alarm as it portrays that one cannot anymore get out of this social quagmire threatening even the outside the world.

Tanghágâ (mystery) pushes the plot further by showing the alien creature painstakingly spreading the bad menace on the entire planet. The scenario is overpowering in a sense that the alien creature has completely ruled over his evil agenda. Banlod (confine) causes a sense of fear as one distrusts each other because of the predicament favoring the alien creature. A distressed angel is seen crying for help because his friend was one of those affected and infested with the manipulation as seen in Tanghaga.

Sablok (yearn) witnesses the lamented angel reporting to the abled guardian of the society that his kinfolk was caught and already manipulated by the alien creature. While holding his child the angel complains to what happened as the abled guardian compassionately listens to her. On a positive note, Sagúkom (embrace) succumbs as goodness triumphs while the world is at the height its peril. The

situation brought out the caring instinct of the inhabitants with one another. The inhabitants begin to be responsible for their upkeep and protection–as long as one remains vigilant and look after beyond himself.

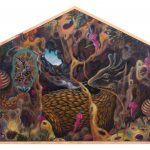

Growing up in Iloilo, Delmo was already exploring these anthropomorphic characters in high school. Delmo was visually honed doing masks and costumes every year for the annual Dinagyang Festival every fourth Sunday of January. Several months prior to the event, he would tag along with choreographers and musicians, they would travel every town researching on local lore, legends and the indigenous expressions of a particular tribe or people. He would hurriedly sketch as they brainstorm on the spot to concoct the plot for the 10-minute at the prized At-Ati dance competition. Each artistic tableau involves history, religion and culture of how the Sto. Niño is venerated to seal the pact between the Datus and the locals. Delmo was able to imbibe the various tribal instincts of the performers. He wanted his designs to be as primarily natural as possible using feathers, beads and sequins and blend well with the audience and environment. Through the years Delmo has acquired his deep Hiligaynon roots and conceptualized his paintings similar to the scene per scene of the Dinagyang epic. This way of story-telling comes second nature to him. No wonder every pictorial frame he churns out is a staged performance in live color. Even his titles are Visayan in origin and scope.

Delmo devises his own paint brushes, sourcing them from discarded chicken feathers. Depending on their application they satisfy his precise brushstrokes and translate his bespoke iconographies. Although his visual style is homegrown he remains to be authentic despite the current art practice today that has evolved into a coy and crass creative exercise.

He is by nature an initiator—wanting to be a trailblazer on his own, away from their conventional modes of mixing paints. With no drawing reference, he usually illustrates from his subconscious straight to an inviting blank white canvas. An early riser, initially he does not yet figure the image yet he knows what it is all about. Delmo is inspired by Hiligaynon words as titles in expounding his ripening world-view. In explaining further, Delmo supposedly feels relief for every concept finished off on canvas—a figurative pierced thorn is taken out of his worries—like an unloaded burden off his back.

Delmo’s realism counters the traditional genres for it to redefine itself into new actualities in its own right. It adheres to that old school of eye to hand skill in service of the imagination. Often eschewing the banal and sacred, it defies fixation with the tested norms. Looking up to his fellow Ilonggo artists as influences, practicing art in the peripheries has taught Delmo new and fresh perspectives he has immortalized with his own distinct and evocative expressions. As if enlightening the viewer, AMPO is striking for its diversity and spontaneity—an in-your-face figurative theater. It has no shared style or desired intentions yet a common thread persists that individually Delmo is capable of imagination and commitment to the craft. His paintings are organically breathing, ethereally impermanent and fixture of contemplation. They continue to grow on you–long after seeing the exhibition and the ongoing pandemic maybe over.